Ancient Corinth, on the Peloponnesian peninsula in Greece, is known primarily to moderns as one of the cities visited by St. Paul and the setting of Paul’s pair of letters to the Corinthians. (First Corinthians is abbreviated I Cor., and Second Corinthians is abbreviated II Cor.) One of the most familiar passages of the Bible, in fact, is the “love passage” of I Cor. 13:1-13, a popular reading at weddings.

Paul’s letters to the Corinthians have been studied and analyzed systematically by scholars for nearly 200 years. Similarly, the ancient site of Corinth has been systematically excavated for the past 100 years. Therefore, we know a great deal about Corinth, Paul, and early Christianity.

An online history of Corinth can be found here, among other websites. Neolithic peoples inhabited the area for the better part of two thousand years (ca. 5000 to 3000 Before the Common Era [BCE]). Most of the prehistoric finds date from Mycenaean (Late Helladic) times (1600 to 1100 BCE); Mycenae lies only about 41 kilometers from Corinth. The antiquity of Corinth is important for a discussion of religious beliefs and practices leading up to the time of St. Paul and the earliest Christians, while archaeological remains that can still be seen today, and which date closer to the time of Paul, gives us a sense of what the city might have been like then.

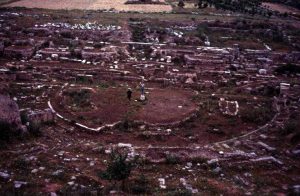

An overview of the site is instructive. The temple of Apollo had been built about 550 (BCE) and the Asklepios sanctuary in the fourth century BCE. In addition, the theater had been constructed in the fifth century BCE [photo left], and the Isthmian games near Corinth had been established in 582 BCE. Paul visited the city in 51-52 of the Common Era (CE). An earthquake devastated the city in 77 CE, but also presented an opportunity to further renovate and rebuild.

An overview of the site is instructive. The temple of Apollo had been built about 550 (BCE) and the Asklepios sanctuary in the fourth century BCE. In addition, the theater had been constructed in the fifth century BCE [photo left], and the Isthmian games near Corinth had been established in 582 BCE. Paul visited the city in 51-52 of the Common Era (CE). An earthquake devastated the city in 77 CE, but also presented an opportunity to further renovate and rebuild.

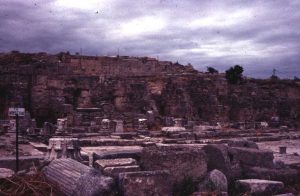

Excavations show that a great deal of construction and expansion occurred in the early years of the Roman Empire, especially in the first half of the second century CE. The Peirene Fountain, named after the daughter of the river god Acheloos, was built in the Roman era. The odeion, a musical facility with a capacity for 3,000 people, was constructed toward the end of the first century CE. The theater was renovated and expanded in both the first and third centuries CE, enabling it to accommodate gladiatorial contests and water events. Shops [photo below] and a number of temples in the forum area appeared in the first and second centuries CE.

Most of the archaeological evidence from the site dates to the Roman era, allowing scholars to know what Paul, his contemporaries and his immediate descendants would have witnessed. The site, including the forum (agora), houses temples to a number of deities (Apollo, Poseidon, Hera/Juno, Athena) and to Octavia, sister of Emperor (Caesar) Augustus; various civic monuments; the Glauke and Peirene fountains; baths; gymnasium; stoas; and basilicas. North of the city, an extensive Asklepieion (sanctuary to the healing god Asklepios) was found, and on the slopes of Acrocorinth, the city’s acropolis, the remains of several temples. The existence of a Jewish community at Corinth is also attested: the Jewish historian Philo, writing in 281-282 CE, mentions Jewish colonies in Corinth “and most of the best parts of the Peloponnese,” an inscription on a lintel, reading “Synagogue of the Hebrews,” and an artifact with a menorah [photo right] have been discovered in the excavations.

The Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Corinth

One aspect of ancient Corinth that has a bearing on the history of Christianity is the other deities worshiped there at the time of St. Paul and in the centuries thereafter. Many of these deities were female, something that may be less well known today. Relatedly, there are also religious remains that provide ample evidence for the involvement of women in cultic activities.

In addition to temples located in the forum, a temple to Demeter and Kore was found on the northern slope of Acrocorinth. According to the Greek travel writer Pausanias, a spring behind the Aphrodite temple on Acrocorinth was linked to the Peirene Fountain. Also, statues to various female deities adorned the forum area, as mentioned above. Pausanias and archaeological remains attest to the existence in the forum area of impressive ones to the Ephesian Artemis [photo left], Nike, Tyche, Aphrodite (the latter two perhaps housed in separate small temples) and Athena (a colossal bronze statue), as well as to male gods Dionysos and Clarian Apollo.

In addition to temples located in the forum, a temple to Demeter and Kore was found on the northern slope of Acrocorinth. According to the Greek travel writer Pausanias, a spring behind the Aphrodite temple on Acrocorinth was linked to the Peirene Fountain. Also, statues to various female deities adorned the forum area, as mentioned above. Pausanias and archaeological remains attest to the existence in the forum area of impressive ones to the Ephesian Artemis [photo left], Nike, Tyche, Aphrodite (the latter two perhaps housed in separate small temples) and Athena (a colossal bronze statue), as well as to male gods Dionysos and Clarian Apollo.

Traditional descriptions of Graeco-Roman Corinth (and earlier) have stressed the importance of the male deities Poseidon, Apollo, Zeus, Helios (the Sun), Asklepios, Pan, and Dionysos. Commentators devote more text and photographs to these male deities than to female ones. No doubt these gods were important to early Corinthians, but recent scholarship and new excavations have shown that several goddesses were indeed prominent at Corinth through the early Christian era and into early Byzantine times.

In addition, Corinth boasts a number of public facilities having to do with water. Water and the worship of female deities have a long history, and the connection still existed in the imperial era, as we shall see.

Aphrodite

Aphrodite was probably the most important of the female deities in the Corinthian region. Corinth was indeed known, in the classical period, as Aphrodite’s city, and she was identified by the late second-century CE writer Alkiphron as “guardian of the city,” at least for its women. Three shrines to her stood in the city and two more in nearby towns. One of her shrines at Corinth, an Ionic temple, was built in the mid-first century CE and was richly adorned with exquisite moldings. Another temple, located near a cypress grove and a cemetery, indicated her connection with the dead – more reminiscent of the all-encompassing deity of prehistory than of the Roman Venus primarily associated with eros, erotic love. Pausanias also described a “temple and a stone statue of Aphrodite” at Cenchreae, home of the deacon Phoebe, whom we will investigate next week.

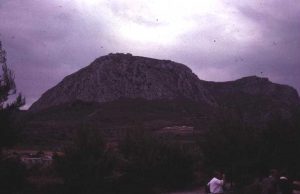

Yet another shrine to Aphrodite, one of the most famous of hers throughout Greece, was located on Acrocorinth [photo right], at which many women served who were dedicated to the goddess their entire lives. Significantly, the source of the Peirene Fountain in Corinth surfaced south of this sanctuary and flowed through an underground channel. Pausanias described the Peirene fountain as follows:

On leaving the market-place (agora) along the road to Lechaeum you come to a gateway, on which are two gilded chariots, one carrying Phaethon the son of Helius (Sun), the other Helius himself. A little farther away from the gateway, on the right as you go in, is a bronze Heracles. After this is the entrance to the water of Peirene. The legend about Peirene is that she was a woman who became a spring because of her tears shed in lamentation for her son Cenchrias, who was unintentionally killed by Artemis. The spring is ornamented with white marble, and there have been made chambers like caves, out of which the water flows into an open-air well. [Pausanias. Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., Book 2, Corinth]

Water and fountains, as we have seen, are strongly linked in both prehistoric and historical periods to the female divinity. The continuity of the Peirene Fountain as a sacred female site is important, and we shall return below to this fountain in our discussion of caves and water.

The large volume of statues, terracotta lamps and figurines representing Aphrodite attests to her popularity and importance at Corinth. Archaeologists have discovered many such remains throughout the site. Not only have objects been found at shrines devoted to her but also at sanctuaries of other deities. Classical-era figurines of Aphrodite have been found in the Demeter sanctuary, and marble statues of her were discovered in the Roman-era Asklepios complex. Terracotta figurines demonstrate her importance to people with limited resources, especially women.

Like other goddesses in the classical, Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman periods, Aphrodite functioned as the city’s protector deity. A shrine from the fifth century BCE in the Potter’s Quarter, near the city walls, may have been dedicated to Aphrodite to protect the fortifications at that point in the wall. During the Persian War, women petitioned Aphrodite for help on the Greek side of the conflict. Later, the historian Pausanias asserted that a statue depicting the goddess as armed was housed in her temple on Acrocorinth. Indeed, this temple became an enduring motif for Corinthian coinage of the Roman period.

These images are, of course, far from those of Aphrodite or Venus the goddess of romantic love. Rather, they point markedly to an image of great importance to people, over a span of time and across the Mediterranean area, socially, religiously and politically. This deity was powerful against natural and human enemies and served not only individual, personal needs but also those of an entire polis. For Corinth, Aphrodite served to solidify the city’s identity far and wide.

The fact that this powerful, influential goddess may have been the chosen deity of women and others of modest means says volumes about the probable influence of those worshipers and their deity on the city’s reputation, renown, and real political power in relation to other cities and colonies. Aphrodite was a female deity, and women worshiped her faithfully for hundreds if not thousands of years. It would seem, then, that the city’s populace, male and female, rulers and ruled, acknowledged the deity’s strength and the women’s power, despite their lower-class status, to preserve and protect its citizens. This was not a goddess worshiped “on the side,” as it were, or petitioned for minor wants and desires. She was, for all intents and purposes, the Supreme Deity of this very important city.

Demeter and Kore

The goddesses Demeter and Kore (Persephone) were also among the city’s most prominent deities. In their temple midway up the north slope of Acrocorinth a great quantity of curse or prayer tablets, as well as female objects, were discovered, indicating a lively cult of women throughout its history, and concern with agrarian fertility. Votive offerings decrease over time, but lamps, curse tablets and fragments of priestess heads take prominence. The lamps appear to signify nocturnal rites, the night being the realm of the goddess (via the moon). Offerings at this shrine in the Graeco-Roman era seem to be of a more perishable nature and food-related, again possibly related to fertility.

Some of these cult practices survived into Graeco-Roman times from the sixth and fifth centuries BCE. Many aspects of the cult, as reconstructed from the archaeological evidence, point to a strong female presence, the centrality of ritual dining, and Demeter’s concern with household matters. At least 14 dining rooms probably existed at the end of the sixth century BCE, accommodating some 100 people. A century later, the number had grown to at least 25 buildings, or 30 rooms, with space for 200 people. As suggested by these numbers, both lay participants as well as clergy dined within the sanctuary.

The dining rooms themselves are small, able to accommodate only five to nine persons at one time. In addition, the theater at the top of the sanctuary could only accommodate 85-90 people at one time. Therefore, attendance was restricted in some way for at least part of the festival. It is probable that “the most common basis for selection was that of gender.” We know from comparable festivals that men were excluded, and in some cases, only married women were allowed. (Bookidis, “Ritual Dining,” 49-50)

However, in the Corinth example, at least five male names are attested in the dedicatory graffiti, and 40 or more terracotta statues from the site depict young men carrying offerings. The evidence leads to the conclusion that “at Corinth it was the women who ate by themselves in the dining rooms, that they reclined on the couches like men and engaged in the same sort of lively conversation.” (Bookidis, “Ritual Dining,” 50)

Archaeologists have found a great deal of evidence as to what was and was not eaten in the sanctuary during the rituals. The main part of the meal appears to be grain; participants apparently ate wheat or barley boiled into a loose porridge or thick paste and probably nuts and fruits. Wine and other beverages were consumed in large quantities. We thus witness the continuing popularity in the Hellenistic era of the adoration of a major female deity – even a major maternal deity and her daughter, in this case – primarily by women. Since some evidence from the sanctuary dates to the Roman era, the cult seems to have continued for several centuries, even into the time of Paul.

Asklepios

The temple of the male god of healing, Asklepios [public domain photo left], provides further evidence for ritual dining from the Graeco-Roman (as well as a connection with the prehistoric goddess, which we will only touch on briefly here). The Asklepios sanctuary was located north of the Corinthian forum. While built in the fourth century BCE, its dining rooms were in use in the Roman period. The rooms were constructed with couches built along the walls on which devotees reclined [photo below]. Near each couch were tables for the food, and in the center of some of the rooms was found a brazier for cooking. Many offerings to the healing god have been found in the temple precincts, including clay models of body parts – heads, hands, feet, breasts, penises – now housed in the on-site museum.

The temple of the male god of healing, Asklepios [public domain photo left], provides further evidence for ritual dining from the Graeco-Roman (as well as a connection with the prehistoric goddess, which we will only touch on briefly here). The Asklepios sanctuary was located north of the Corinthian forum. While built in the fourth century BCE, its dining rooms were in use in the Roman period. The rooms were constructed with couches built along the walls on which devotees reclined [photo below]. Near each couch were tables for the food, and in the center of some of the rooms was found a brazier for cooking. Many offerings to the healing god have been found in the temple precincts, including clay models of body parts – heads, hands, feet, breasts, penises – now housed in the on-site museum.

While Asklepios was a male deity, his cult had parallels and overlaps with those of female deities. First, as noted above, marble statues to Aphrodite were found in this sanctuary. Second, the goddess Hygeia had been the primary healing deity before being eclipsed by Asklepios. Hygeia and her sister Panacea may have been personifications of the Great Mother Goddess’ breasts. Also, the Greek caduceus – the staff with the entwined snake, the international symbol of the medical profession – was displayed in the healing temples of Hygeia and Panacea and represented physical and spiritual healing. As goddess of mental health, Hygeia often worked through dreams.

Third, in most healing cults in antiquity, water played a crucial role, and water was associated with the female in a basic, primordial fashion. Water played a large role at the Corinthian Asklepios cult: the Lerna well on the site provided water to worshipers, who drank of it in hopes of a cure, and a significant bath complex of late antiquity was located beside the sanctuary.

The Asklepios cult at Corinth was obviously important to the city, not only for its inhabitants, but also for pilgrims seeking healing. At the time of his visit, Paul almost certainly knew of the Asklepieon and its related structures nearby. The inner workings of the Asklepieion were well known to the general public. People went to the Asklepieon to have therapeutic dreams, to receive advice about their illnesses. As with most other religious events, fasting was required before the dream. Temple priests interpreted dream(s), then the person could stay for several days in the temple, as a place of solitude and rest, or the person could leave. This supplication to gods by people wanting something is sharply contrasted by the Christian healing practices of one man, Jesus, healing someone primarily through God’s mercy and compassion.

Caves and Water

Two natural phenomena – caves and water – play a large role in the religious heritage of Corinth and environs, both in prehistoric and into Graeco-Roman times. Caves were believed by ancients to be the womb of Mother Earth, while water was her life-giving fluid. Excavations in Corinth and in the region around the city have yielded a number of natural caves, some of which were used ritualistically and others of which were used for funerary purposes.

It was not only at the Asklepios sanctuary that water was important at Corinth. In fact, water was used extensively for cultic purposes in both the Greek and Roman eras. Excavations have yielded remains from at least four public baths and four fountains in Corinth proper, including the Lerna, mentioned above. The Glauke Fountain was hewn into the rock near what later became, in the first century CE, a temple consecrated to Hera Akraia (Juno dwelling on the heights). The Glauke Fountain, probably named for the daughter of the mythical king Kreon, was apparently built in the sixth century BCE and has its source at the foot of Acrocorinth. It continued in use into the Graeco-Roman era.

The Peirene Fountain [photo left], named for the daughter of the mythical river God Acheloos, was in use by at least the seventh century BCE. According to the myth, Peirene “turned into a fountain so as to be able constantly to lament the death of Kenchrias, her son, whom the goddess Artemis had inadvertently killed.” (Penteas, Corinth, 31-32) The fountain’s forecourt terminates in six entrances, which in turn “communicate with little caves which were turned into ‘rooms.’” The forecourt was sumptuously decorated with statues and monuments made of white marble, and the fountain remained in use into Byzantine times.

The Peirene Fountain [photo left], named for the daughter of the mythical river God Acheloos, was in use by at least the seventh century BCE. According to the myth, Peirene “turned into a fountain so as to be able constantly to lament the death of Kenchrias, her son, whom the goddess Artemis had inadvertently killed.” (Penteas, Corinth, 31-32) The fountain’s forecourt terminates in six entrances, which in turn “communicate with little caves which were turned into ‘rooms.’” The forecourt was sumptuously decorated with statues and monuments made of white marble, and the fountain remained in use into Byzantine times.

The source of the Pierene fountain was south of the sanctuary of Aphrodite on Acrocorinth. An underground channel carried the water to the agora. The waters of this fountain, then, are connected with a river god and two powerful goddesses, Aphrodite and Artemis.

In addition to Corinth proper, baths, bath complexes and other water-related structures have been found elsewhere in the region. A Roman bath from the early fourth century has been found near the modern town of Zeugolatio, south of Aghios Charalambos church. A sizable subterranean water tunnel has been found at Bayevi, and Roman shards and possibly other remains were discovered nearby. A nympheum from the third through sixth centuries CE has been found at Lechaion, Corinth’s western port; significantly perhaps, this is also the site of the “largest basilica ever in Greece and in the world at its time.” (Rothaus, Corinth, 153)

Obviously water would have been an essential commodity at any ancient city: without it people could not drink, bathe or cultivate. However, at Corinth as at other ancient sites, water and its sources had intentional religious connections and connotations as well. In the Greek, Roman and early Christian eras, water was associated with nymphs, mythical figures, powerful goddesses, healing, and communal and ritual dining. The fact that many water-related finds at Corinth were so closely aligned with cult and ritual, and that there was continuity in the cult practices through the period of Corinth’s presumed destruction, shows that water was still believed to be a sacred life-giving substance and related to the earth, the primordial Mother. It was to be used but not abused, and it was to be revered as life itself.

When analyzing the writings of St. Paul and other early Christian literature, we must always remember the wider social context, especially as revealed through archaeology. This social context includes evidence for powerful goddesses. It also includes the role and status of women, which we will examine next week in relation to ancient Corinth.

Resources

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Goddess and God: A Holy Tension in the First Christian Centuries. Marco Polo Monographs 10. Warren Center, PA: Shangri-La Publications, 2006.

Bassler, Jouette M., “Phoebe.” Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 134-35. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Bassler, Jouette M., “Prisca/Priscilla.” Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 136-37. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Bookidis, Nancy. “Ritual Dining at Corinth.” Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches. Ed. Nanno Marinatos and Robin Hägg. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

Bookidis, Nancy, Julie Hansen, Lynn Snyder, and Paul Goldberg. “Dining in the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore at Corinth,” Hesperia, Vol. 68, No. 1 (January-March 1999) 1-54.

“Corinth.” Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. F.L. Cross. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, 417-18.

Engels, Donald. Roman Corinth. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago, 1990.

Finegan, J. “Corinth.” Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Vol. 2, 682-84. New York and Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1962.

Friesen, Steven J., Daniel N. Schowalter, and James C. Walters, editors. Corinth in Context: Comparative Studies on Religion and Society. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010.

Lanci, John R. A New Temple for Corinth: Rhetorical and Archaeological Approaches to Pauline Imagery. New York, etc.: Peter Lang, 1997.

Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome, O.P. St. Paul’s Corinth: Texts and Archaeology. Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier, Inc., 1983, 1987.

Økland, Jorunn. “The Curse Tablets of Demeter and Kore (Room 7) – Evidence of Women’s Rituals?” paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, Boston, MA, November 1999.

Økland, Jorunn. Women in Their Place: Paul and the Corinthian Discourse of Gender and Sanctuary Space. London and New York: T & T Clark International, 2004.

Oster, Richard E., Jr. “Corinth,” Oxford Companion to the Bible, eds. Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, 134-35. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Penteas, Ev. Corinth, Mycenae, Argos, Tiryns, Nauplion, Epidaurus. Athens: I. Sideris Bookshop; no date; ca. 1980.

Reis, Patricia. Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. New York: Continuum, 1991.

Rothaus, Richard M. Corinth: The First City of Greece. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill, 2000.

Themelis, Petros G.Ancient Corinth: The Site and the Museum. Athens: Editions Hannibal, no date, ca. 1980.

Thompson, C.L. “Corinth,” The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, Supplementary Volume, 179-80. Nashville: Abingdon, 1976.

Wickkiser, Bronwen L. “Asklepios in Greek and Roman Corinth,” in Friesen, Steven J., Daniel N. Schowalter, and James C. Walters, editors. Corinth in Context: Comparative Studies on Religion and Society, 37-66. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010.

Corinth photo credits: Valerie Abrahamsen