Philippi in northern Greece is an important city for the history of Christianity and a fascinating archaeological site. Here we will highlight a few features that raise important issues for modern contemplation, since Christianity has had such vast influence on the West. I will illustrate these points using photos of mine taken on site during the years I was completing my doctoral dissertation at Harvard Divinity School.

The Greek goddess Artemis – who was also the Roman goddess Diana – was worshipped at Philippi for generations, starting in the prehistoric period and continuing into the early Christian era. The worship of Artemis at Philippi and elsewhere was linked to her roles as protector of children and of women in childbirth, goddess of healing, and guardian of the afterlife.

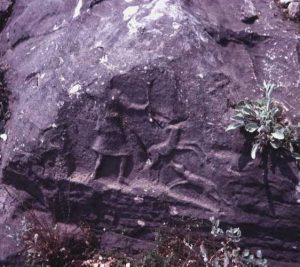

Well after the time of Paul, around 200 CE, worshippers (probably women) carved reliefs into the live rock of the hill above the town’s theater. (These reliefs were the focus of my research.) The reliefs exhibit a female to male ratio of seven to one. The figure portrayed most frequently is Artemis/Diana, followed closely by unidentified women, probably priestesses (an example in the photo).

This shows that, despite the visit of Paul and the growth of Christianity throughout the empire in the first few centuries, paganism, including the worship of female deities, remained strong. While there were sporadic persecutions of Christians, they coexisted peacefully with pagans and, in some communities, Jews during this time.

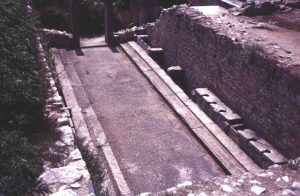

This overview of the Philippi forum, which dates to the second century and later and is a current archaeological site, shows the remains of the ancient library, several temples to emperors and empresses, and the Via Egnatia (a road on which Paul and others would have traveled, which ran from Constantinople in the East to Dyrrachium and Apollonia, Illyria [in present-day Albania]). The overview also shows the remains of several significant basilicas from the early fourth to the sixth centuries (more below). The forum (Greek “agora”) that Paul and his contemporaries would have seen lie under the visible archaeological features.

This overview of the Philippi forum, which dates to the second century and later and is a current archaeological site, shows the remains of the ancient library, several temples to emperors and empresses, and the Via Egnatia (a road on which Paul and others would have traveled, which ran from Constantinople in the East to Dyrrachium and Apollonia, Illyria [in present-day Albania]). The overview also shows the remains of several significant basilicas from the early fourth to the sixth centuries (more below). The forum (Greek “agora”) that Paul and his contemporaries would have seen lie under the visible archaeological features.

In antiquity, latrines afforded much less privacy than we enjoy today. The latrines at Philippi are among the best preserved in the ancient world. Water from the acropolis hill (now dried up) would have flowed continuously through the plumbing to flush the system. Male and female patrons, who wore non-fitting clothing unlike ours, used sponge systems to clean themselves. The latrines were among the locales where news and gossip (probably including religious and political rhetoric) were exchanged.

In antiquity, latrines afforded much less privacy than we enjoy today. The latrines at Philippi are among the best preserved in the ancient world. Water from the acropolis hill (now dried up) would have flowed continuously through the plumbing to flush the system. Male and female patrons, who wore non-fitting clothing unlike ours, used sponge systems to clean themselves. The latrines were among the locales where news and gossip (probably including religious and political rhetoric) were exchanged.

Mosaic floor, Octagon complex

The so-called Octagon complex, to the east of the forum (on the left side of the overview photo), is a fascinating and important archaeological structure. The Octagon – a baptistery, priests’ quarters, bath complex and a guest house for pilgrims – dates to the mid-fifth century. However, its history dates much earlier, probably to around 313 CE. (This date is important in the history of Christianity: the Edict of Milan, promulgated in February 313, was an agreement that Christians would be treated benevolently within the Roman Empire.) An important mosaic inscription from this earliest stage of the building states, “Bishop Porphyrios has done the mosaics of the (St.) Paul Basilica for Christ.” Bishop Porphyrios attended the Council of Sardica, held around 344 CE, so this inscription refers to a person whom we know from historical records. In fact, according to archaeologist Charalambos Bakirtzis, this church was “the earliest known public assembly hall for Christians that can be dated with some certainty.” The reference to St. Paul reflects the connection between Paul and Philippi, a connection known from both the letter to the Philippians and Acts of the Apostles 16 in the New Testament.

The baptismal font in the shape of a cross is an intriguing and attractive feature of this complex.

This original “basilica” was most likely a privately-owned martyrium, that is, a structure to honor a deceased hero. Located in close proximity to this structure was a Hellenistic tomb or heröon, still being used as the locus of a local hero cult. Over 1,000 bronze coins dating from the fourth to sixth centuries CE were found on and around this heröon, and the bodies of young children were buried in the courtyard of the Octagon.

Martyria in antiquity were often constructed in the shape of an octagon (the shape of this “basilica” in its second and third phases). The octagonal shape, along with the inscription, the coins, the tomb, and the buried children, all merge to demonstrate that pagans and Christians were sharing religious space in a peaceful manner, as was happening throughout the empire. According to Bakirtzis, it was very possible that Philippi “possessed at least some of [Paul’s] relics,” suggesting the strong possibility that, by the fourth century, Philippians (and pilgrims who traveled there) may well have been honoring the deceased person in the tomb as St. Paul (Bakirtzis and Koester, 47).

Direkler means “columns” in Turkish. In the 19th century, only this structure was visible at Philippi and indicated to early archaeologists where they should excavate. This basilica was constructed around 550 CE on top of the ruins of a large building south of the forum. The archaeologists surmise from the evidence that the dome of the building collapsed before it could be dedicated, but it boasts a number of beautiful and significant features.

- Several surviving capitals have lovely decorations of acanthus. The corresponding cornices are decorated with fish, mollusks and vegetable motifs.

- Marble slabs and sculpted plaques would have covered the walls and floors.

- A number of Christian graves dating to the fourth to sixth centuries were found in the floor. Two of six inscriptions associated with these graves are suggestive of same-sex missionary couples, a phenomenon found elsewhere in antiquity.

- The building’s size, the originality of its architectural form and its decorative features make it unique among known basilicas in Greece.

With the Octagon and other features at Philippi we witness a significant transition time in the history of Christianity; the religion is beginning to come into its own architecturally, it is becoming respected in the highest levels of government, it is co-existing with non-Christian religious groups and practices, and it is attracting followers. Many individuals held onto their old beliefs even as they started to embrace the Christ cult. By the fifth and sixth centuries, Christianity was the religion of the empire, and Philippi was on the map with six basilicas being constructed (and reconstructed) in the town within two or three centuries. The diversity of the religious landscape in antiquity, late into the so-called Christian era, not only makes this a fascinating field of study but should also give us pause: none of us has cornered the market on the whole truth, and sometimes keeping the peace between divergent views, especially on some of our most important issues as human beings, is vastly more important than promulgating our own viewpoint.

Resources

Abrahamsen, Valerie. “Burials in Greek Macedonia: Possible Evidence for Same-Sex Committed Relationships in Early Christianity,” Journal of Higher Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall 1997) 33-56.

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Women and Worship at Philippi: Diana/Artemis and Other Cults in the Early Christian Era. Portland, ME: Astarte Shell Press, 1995.

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. “Women Artisans in the Service of the Church,” Sisters Today, Vol. 65, No. 2 (March 1993) 96-103.

Bakirtzis, Charalambos and Helmut Koester, eds. Philippi at the Time of Paul and after His Death. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1998.

Boswell, John. Same-sex Unions in Premodern Europe. New York: Villiard Books, 1994.