Traditional Christian judgmentalism – the notion that only those who believe in Jesus as their personal Lord and Savior will go to heaven when they die – originates in part from the New (Christian) Testament lesson that was read in many churches on Sunday, July 23, 2017. The lesson is from the Gospel of Matthew, Chapter 13, verses 24-30 and 36-43, and is reprinted below.

The text is fairly straightforward. The wheat is good, but the weeds, which have been sown by an enemy, are bad. The slaves/servants are told not to pull the weeds up until the harvest because doing so will uproot the wheat at the same time. It is when the harvest comes that the weeds can then be pulled, bound and burned. The author of the Gospel then has Jesus explain the parable. The sower of the good seed is the Son of Man (that is, the Christ figure); “the field is the world, and the good seed are the children of the kingdom [of God]; the weeds are the children of the evil one, and the enemy who sowed them is the devil; the harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are angels.” This passage can be viewed as starkly black and white: there is good and evil in the world, and you better side with the Son of Man and not the devil or you’ll “burn” at the end of the age.

The parable can be interpreted in other ways that make some sense. My rector, for instance, interpreted it psychologically: the wheat and weeds are the positive and negative things about each of us. None of us is perfect, and the good and bad within us will coexist until the end of time – and that’s not a horrible thing.

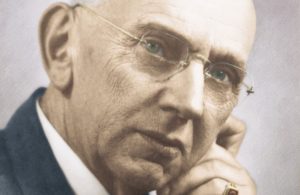

I would like here to bring in a perspective from paranormal research, a perspective hardly ever heard from the pulpit, I would venture to say. What emerged from the Life Readings of seer Edgar Cayce at the beginning of the 20th century, for instance, is the fact of reincarnation and its cognate, karma, or the law of cause and effect. While reincarnation was a fairly widely-held belief in the ancient world, it does not appear – at least not explicitly – in the NT. The story of how reincarnation disappeared from the NT is significant and important.

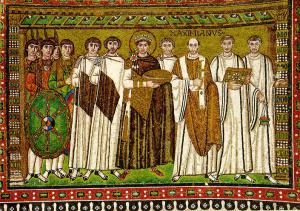

Noel Langley in Edgar Cayce on Reincarnation traces the elimination of reincarnation to the abuse of power exerted by the Emperor Justinian and his wife Theodora. (Hang on: this gets a little complicated.) Justinian “summoned the Fifth Ecumenical Congress of Constantinople in 553 A.D. [CE] to condemn the Platonically inspired writings of Origen.” Theodora, a very devious woman, became a convert to the controversial doctrine espoused by the Monophysites, a sect that contended that Jesus’ physical body was wholly divine. This doctrine completely rejected the teachings of the church father Origen (ca. 185-254 CE), which included the argument that Jesus was both human and divine. While the Chalcedonian Decree of 451 CE protected the teachings of Origen, and while Justinian supported this decree, Theodora and the Monophysites set about expunging all Biblical references to reincarnation. Theodora’s motive seems to have been to bolster her megalomaniacal hope for “instant apotheosis upon departing this life.”

Langley goes on to explain other machinations of Theodora, which probably included having two Popes killed. Langley states, “Theodora, having contrived the murder of two Popes, expected to instill their successor Vigilius with her own mania for exterminating all traces of the Chalcedonian Decree and its division of Christ into two separate entities, human and divine. She failed.”

However, after her death, Justinian remained under her influence. In 531, the same year as the Chalcedonian Decree, he issued the Three Chapters Edict, a little-known ruling that was recognized by Pope Vigilius and the four Popes who followed him. This Edict was ostensibly an attack on Origen and all theologies that depended on his writings, but was apparently never really ratified by the entire church body. During the period when it was believed that the church was condemning Origen, most references to reincarnation were apparently deleted from Gospel manuscripts, according to Langley: “Justinian’s deletions and alterations of the Gospels would have been completed in very short order, and so would the elimination of all and any evidence of the vandalism.”

It appears that the church never scrutinized the workings of the Fifth Ecumenical Council to examine what was actually enacted, which had the effect of the church – both West and East after the split of 1054 – coming to accept Origen, for the most part. What was not realized, or what was suppressed, was that Origen’s writings included support for reincarnation. Therefore, the church thought mistakenly that it had condemned Origen, with the result that the notion of the preexistence of the soul, and, by implication, reincarnation was excluded from Christian belief. Reincarnation was ultimately condemned implicitly by the Councils of Lyons in 1274 and Florence in 1439, “which affirmed that souls go immediately to heaven, purgatory, or hell” (“Metempsychosis,” Oxford, 908). This is what Christianity, and thus the West, has lived with since the Middle Ages.

The paranormal research shows that reincarnation – expunged from Biblical texts and substituted with Theodora’s megalomaniacal creed – is intimately linked with the law of cause and effect, or karma. That is, paraphrasing the parable in Matthew, “we reap what we sow.” Our thoughts and deeds that help others assist our soul’s progress; our thoughts and deeds that harm others, however, must be made right. This means that our souls must return to earth in different bodies, over millennia, to repay those we have wronged, to do additional good for the world, and to continue on the path of spiritual growth. Note that scientific research and techniques on paranormal phenomena, the work of reputable psychics and mediums, and evidence from near-death experiences and out-of-body experiences all support the conclusions about reincarnation and karma from the Cayce readings.

It seems highly likely, therefore, that the earliest hearers of Jesus’ parable about the wheat and weeds (probably in an oral form, not written) could well have understood it in the context of the law of cause and effect. The wheat is our good deeds that keep us on the trail of spiritual growth. The weeds are our harmful, perhaps “evil,” deeds – deceit, greed, rape, revenge, robbery, exploitation, murder. The “burning” of bundles of weeds at the end of time would be understood as the point at which our souls unite with Divine Love, which is actually the destination of all souls. Jesus’ hearers may well have experienced him as a highly-developed soul and wise teacher who knew at profound levels the actuality of many earthly lives.

It seems highly likely, therefore, that the earliest hearers of Jesus’ parable about the wheat and weeds (probably in an oral form, not written) could well have understood it in the context of the law of cause and effect. The wheat is our good deeds that keep us on the trail of spiritual growth. The weeds are our harmful, perhaps “evil,” deeds – deceit, greed, rape, revenge, robbery, exploitation, murder. The “burning” of bundles of weeds at the end of time would be understood as the point at which our souls unite with Divine Love, which is actually the destination of all souls. Jesus’ hearers may well have experienced him as a highly-developed soul and wise teacher who knew at profound levels the actuality of many earthly lives.

Denying reincarnation and karma enables Christians (and, consequently, Westerners) to believe that we will not have to pay for our misdeeds. For victims of violent crime, for instance, this cannot be in any sense a measure of justice; it is instead a great betrayal.

Further, the denial of reincarnation and the immortality of the soul also helps instill in some modern Westerners the fear (perhaps subconscious) of total annihilation at death, a fear (or hope?) that has wide-ranging ethical and societal consequences. If we think that what we do to others is irrelevant and that at death we either no longer exist or, like Theodora, we automatically and completely go to the heavenly realms, we open the door to unethical behavior and even violence. The acknowledgment of reincarnation and karma, on the other hand, is not only supremely hopeful, for those willing to strive for spiritual growth, but also comforting for those who have been hurt: there is definitely a measure of justice in the cosmos. The belief in reincarnation and karma also enables us to focus our lives on our deeds, not on specific religious beliefs that do not necessarily align with a modern, secular culture.

Matthew 13:24-30, 36-43

24 He [Jesus] put before them another parable: “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to someone who sowed good seed in his field; 25 but while everybody was asleep, an enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat, and then went away. 26 So when the plants came up and bore grain, then the weeds appeared as well. 27 And the slaves of the householder came and said to him, “Master, did you not sow good seed in your field? Where, then, did these weeds come from?’ 28 He answered, “An enemy has done this.’ The slaves said to him, “Then do you want us to go and gather them?’ 29 But he replied, “No; for in gathering the weeds you would uproot the wheat along with them. 30 Let both of them grow together until the harvest; and at harvest time I will tell the reapers, Collect the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned, but gather the wheat into my barn.’” 36 Then he left the crowds and went into the house. And his disciples approached him, saying, “Explain to us the parable of the weeds of the field.” 37 He answered, “The one who sows the good seed is the Son of Man; 38 the field is the world, and the good seed are the children of the kingdom; the weeds are the children of the evil one, 39 and the enemy who sowed them is the devil; the harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are angels. 40 Just as the weeds are collected and burned up with fire, so will it be at the end of the age. 41 The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will collect out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all evildoers, 42 and they will throw them into the furnace of fire, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. 43 Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. Let anyone with ears listen!

Resources

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Paranormal: A New Testament Scholar Looks at the Afterlife. Self-published, 2015. Printed by Shires Press, Manchester Center, Vermont.

Furst, Jeffrey. Edgar Cayce’s Story of Jesus. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1968.

Langley, Noel. Edgar Cayce on Reincarnation. New York: Warner Books, Inc., 1967. See especially pages 179-201.

“Metempsychosis,” F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 908. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Semkiw, Walter, MD. “Reincarnation, Jesus, the Bible, New Testament & Christian Doctrine, http://www.iisis.net/index.php?page=semkiw-reincarnation-past-lives-christianity, accessed July 27, 2017.