The World Happiness Report is out for 2019. Is there anything we can learn from the current top three “happiest countries in the world” and their health care systems, especially as compared to our own in the United States? Is there a way to see how health care systems and citizen happiness are related?

We have discussed the World Happiness Reports in the past, and several nations have consistently ranked near the top since the first Report in 2012: Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden. In 2019, the top three countries are Finland, Denmark, and Norway. Switzerland ranks 6th, and Sweden is 7th. This is not far off from the results of the 2018 report: “Finland ranked as the happiest country,… followed by Norway, Denmark, Iceland and Switzerland.”

We have discussed the World Happiness Reports in the past, and several nations have consistently ranked near the top since the first Report in 2012: Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden. In 2019, the top three countries are Finland, Denmark, and Norway. Switzerland ranks 6th, and Sweden is 7th. This is not far off from the results of the 2018 report: “Finland ranked as the happiest country,… followed by Norway, Denmark, Iceland and Switzerland.”

As we noted before, the US has never ranked higher than 11th since 2012. Alarmingly, the US fell from 14th in 2017 to 18th in 2018; this year, the US has fallen to 19th.

With health care a top issue among Americans, first in the 2018 election cycle and still current as we head into 2020, and with a certain amount of (perhaps confusing) talk about “socialism,” single-payer health care systems, and similar concepts, it might be an interesting exercise to see, at least superficially, how health care systems and health care delivery relate to (if not influence) the happiness of a country’s citizens.

As many Americans are beginning to realize, if they have not realized it before, our health care system (not necessarily the health care we individually receive from our practitioners) is extremely expensive and exceedingly inefficient – with worse outcomes – than the systems enjoyed by most of the other advanced democracies of the world. While the systems in each of the “happiest” countries are complex, it is vital to note that they all have their own unique ways of running and managing those systems. Therefore, it is entirely possible for the US to create our own unique system – perhaps mixing and matching elements of the most successful of the other countries’ systems – that would work well for us. In other words, despite criticism that the debate occurring now among progressives and Democratic leaders shows worrisome division about what to do with our system, the debate is or potentially can be quite healthy (no pun intended). Robust debate as long as the ultimate goal is the same – to provide excellent health care to all Americans – is positive and can get us much closer to where we want and need to be.

So let us look at the three top happiest countries vis-à-vis health care systems, all of which are universal and publicly funded. Here, in the interests of time and simplicity, we will highlight a few points and provide links to the details.

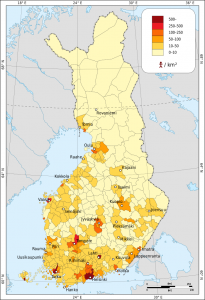

Finland. “The child mortality rate in Finland is one of the lowest in the world; the infant mortality rate is below 4%. The life expectancy for women is 81 years, for a man, 73 years. . . Finland spends less than 7% of its gross national product on healthcare, one of the lowest among EU member states.” The Finnish system is said to be excellent and highly popular. On the flip side, with an aging population and fewer workers in the country to support generous government programs, Finland is showing signs of stress around health care and other issues. Stay tuned!

Denmark. “In 2016, the Danish healthcare expenditure amounted to $5,205 U.S. dollars per capita (approximately 10.4 percent of GDP), with around 84.0 percent of healthcare expenditure being funded by governmental or compulsory means.” (By comparison, “Per capita spending on health care [in the US in 2016] increased by $354, reaching $10,348. The share of gross domestic product devoted to health care spending was 17.9 percent.”) In terms of financing, “[i]n general, all health and social services [in Denmark] are financed by general taxes and are supported by a system of central government block grants, reimbursements and equalization schemes.”

Denmark. “In 2016, the Danish healthcare expenditure amounted to $5,205 U.S. dollars per capita (approximately 10.4 percent of GDP), with around 84.0 percent of healthcare expenditure being funded by governmental or compulsory means.” (By comparison, “Per capita spending on health care [in the US in 2016] increased by $354, reaching $10,348. The share of gross domestic product devoted to health care spending was 17.9 percent.”) In terms of financing, “[i]n general, all health and social services [in Denmark] are financed by general taxes and are supported by a system of central government block grants, reimbursements and equalization schemes.”

Over two million Danes purchase complementary voluntary insurance on an individual basis to pay primarily for pharmaceutical and dental copayments and “services not fully covered by the state (e.g., physiotherapy).” The insurer is a not-for-profit organization, Danmark. Also, nearly 1.5 million Danes obtain expanded access to private providers through supplementary insurance, with policies sold primarily by seven for-profit insurers through private employers as a fringe benefit.

Norway. The bulk of the cost of health care is borne by the state through tax revenue, and “coverage is universal and automatic for all residents. . . Private health insurance is provided by for-profit insurers and purchased for quicker access and greater choice of private providers. It covers less than 5 percent of elective services; it does not cover acute services. About 9 percent of the population, or nearly 15 percent of the workforce, has some kind of private insurance.”

Life expectancy in 2018 in Norway was 80.01 (compared to 79.25 in the US). The infant mortality rate for Norway in 2017 was 2.5 deaths per 1,000 live births (compared to 5.8 for the US).

As we can see, the government-run systems in the “happiest countries” lead to excellent results for their citizens on a number of measures. Now let us examine some of the possible results or consequences if businesses, families, workers and individuals in our own country did not have to worry about their health and the cost of their care on a nearly daily basis:

- According to Ann Troy, MD, FAAP, writing for Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), our people would be healthier – they would not have to skip medical appointments or stop taking needed drugs due to cost. “According to the World Health Organization [as cited by Troy], we are No. 37 on overall measures of health” – that is shameful.

- Relatedly, according to the PNHP, when people do not make their appointments or take their medications, “their illnesses and problems become more deep-rooted and more difficult to treat.” Death is even sometimes the result.

- Infants and children would get a much better start in life – which would no doubt make their parents and caregivers less stressed, if not also happier.

“People would have a wider choice of doctors and would not have to change their doctors every time they change jobs or their employer finds a cheaper health plan,” leading to more continuity of care (PNHP).

“People would have a wider choice of doctors and would not have to change their doctors every time they change jobs or their employer finds a cheaper health plan,” leading to more continuity of care (PNHP).- “More people would receive vaccines and preventive care,” including mental illness and addiction (PNHP). This would positively impact public health.

- “As Karen Christensen, Copenhagen native, explained, ‘The Danish people may appear happier, but this is a direct result of our society’s social security net — it just takes off pressure on a day-to-day basis.’”

- Businesses – small and large – would not have to worry about paying health “benefits” to their employees. They might have to take steps to deduct fees from employees’ paychecks to finance a government-run system, but they are already deducting fees now, in often very complex ways.

- US companies “are at a disadvantage compared with companies in other developed countries which are not saddled with the high cost of providing health care for their employees” (PNHP). Smaller companies in particular “can’t compete for the best employees because they can’t afford to provide health insurance. Unhappiness over health benefits is the leading cause of labor unrest.”

- Bankruptcies due to health care reasons would be reduced, perhaps drastically. “Half of all bankruptcies in the U.S. (approximately 1 million a year) are due to medical debt” (PNHP).

- Costly administrative expenses would be reduced, according to the PNHP. “Dealing with insurance companies is so cumbersome that we have created intermediary entities (such as IPAs) to deal with them. It is estimated that American hospitals spend about 25 percent of their budget on administration, most of it insurance generated! Layers and layers of costly administration would disappear under a single-payer system.”

- If workers have choices in the way they make a living, they might take other positions, become an entrepreneur or gain additional education or training rather than “stay in jobs they hate” because they would not have to worry about health insurance (PNHP).

- Workers’ compensation fraud would probably be reduced. “Some employees commit workers’ comp fraud to gain access to care” (PNHP).

- Workers’ strikes based on health care issues would most likely be reduced.

Obviously happiness is not determined by just one factor like health care. The three happiest countries in the world have many other programs, policies and mere cultural factors in place that lead to their citizens’ positive outlook on life. What providing a robust, workable, efficient health care system would do in the US would be to reduce or even eliminate a major stressor that plagues our individuals, families, workers and companies. Despite current challenges in Europe and other nations to their 70-year-old social safety net programs, the overall take-away should be clear from the evidence: their way is far superior to ours, and we need to learn from them – now.