As we have noted on several occasions, Western civilization as we know it emerged in a polytheistic (multi-deity) environment from the earliest times. The beginnings of the West as we know it today can be traced to the Middle East. The Jewish man Jesus of Nazareth lived from about 4 BCE (Before the Common Era) and died by Roman crucifixion about 30 CE (Common Era), after which his followers proselytized throughout the Roman Empire and eventually caused the Empire to become Christian. Jesus, his family, his followers, St. Paul, and his followers were all Jews; Judaism was a multi-faceted religion and was surrounded by long-established pagan deities, both male and female.  For better or worse, the Christian religion later came to predominate as explorers from the so-called Old World crossed the seas and conquered the so-called New World; unfortunately, the history of the West includes not only exploration but also genocide, colonialism, enslavement, antisemitism, conquest, violence and war.

For better or worse, the Christian religion later came to predominate as explorers from the so-called Old World crossed the seas and conquered the so-called New World; unfortunately, the history of the West includes not only exploration but also genocide, colonialism, enslavement, antisemitism, conquest, violence and war.

The “winners” of conflicts and movements are the ones that usually tell the stories that survive and are passed down. The Christian stories that ultimately shaped Western civilization were, for the most part, written, disseminated and interpreted by male priests in “orthodox” church settings. However, there is always at least one other side to the story. It has become apparent over the past few decades or so that there are alternatives to the dominant Christian narrative. While millions of people around the world adhere to one type of Christianity or other, research is revealing the richness and diversity of Christianity as it developed. Here and in our next post we will specifically explore some Christian practices – actions taken by people calling themselves Christian, especially actions in church services (liturgies) and in other settings that have meaning to those taking the actions.

As we have done before, we will use both archaeological and literary evidence. In this post, we will examine practices and liturgies that are familiar to Christians (and many Westerners) through weekly public services in churches. In our next post, we will examine practices that are less familiar or at least less frequent: special liturgies and miscellaneous practices. We will see how the ancient roots of modern and traditional Christian practices can perhaps offset some of the negative effects that the worst aspects of Christianity have brought about and even offer hope for the future.

As we have done before, we will use both archaeological and literary evidence. In this post, we will examine practices and liturgies that are familiar to Christians (and many Westerners) through weekly public services in churches. In our next post, we will examine practices that are less familiar or at least less frequent: special liturgies and miscellaneous practices. We will see how the ancient roots of modern and traditional Christian practices can perhaps offset some of the negative effects that the worst aspects of Christianity have brought about and even offer hope for the future.

Sunday Liturgies

In most mainstream Christian denominations/branches, the main liturgy transpires on Sundays. Sunday is not the only day of the week in which Christian services take place, but for simplicity we will focus primarily on actions that take place during the liturgies, which generally occur on Sundays.

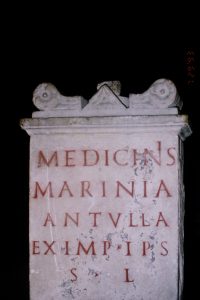

The altar is central to many religious faiths, and there are a number of practices associated with it. In the Christian context, we set the altar, we place things on the altar, including the linens in the appropriate colors, depending on the season, we cense the altar at certain times, we bow to the altar, the priest and her assistants stand at and speak from the altar, and the congregation presents offerings to the altar. On Maundy Thursday before Easter, many of our churches strip the altar in a darkened sanctuary to prepare for Jesus’ death on Good Friday. Some of these actions were inherited from pagan ritual, while others are different.

[Altars pictured here: (right) an altar to a woman doctor from the Römisch-Germanisches Museum in Cologne, Germany, 2nd c. CE.

(left) an altar to Mother Goddesses from the Yorkshire Museum in York, England (43-410 CE)

(left) an altar to Mother Goddesses from the Yorkshire Museum in York, England (43-410 CE)

And (right) the Dionysos altar from Athens (mid- to late-sixth century BCE).]

Most altars in antiquity were set up in front of the temple. People believed that they needed to thank or placate the deities associated with the temple, so priests and priestesses burned animal and bird sacrifices on the altar to feed the gods. The meat was then distributed to the people as food; sometimes bread or vegetables were burned and distributed. (Ferguson, passim) Obviously these things cannot be done indoors.

Horns on the altars were a very common feature.

- The meaning is a little vague, but the horns may originate in a female context: the stag or deer is associated with Artemis/Diana, the huntress.

- Bulls’ horns, which we usually associate with masculinity and male strength, represented regeneration in Neolithic times (Old Stone Age) because they resemble women’s anatomy.

- The fire that burned the offerings on the altar was linked to female practices: it was primarily the woman of the household who was responsible for keeping the home fires burning on the domestic hearth, and in Rome, the Vestal Virgins’ essential chore of tending the “eternal fires” of the Empire was similar; the goddess “Vesta’s altar flames were never allowed to go out, for that would bring down the empire” (Walker, 227).

While we do not see horns on the altars in today’s Christian churches, we should keep in mind that altars in our ancient ancestors’ times were closely associated with the female side of life. While Christianity co-opted these ancient symbols and actions, putting the altar and its actions in an almost exclusively male context, the fuller story is richer than that, and we can perhaps try to reclaim some of the ancient wisdom on behalf of the common good. We will return to this theme again and again.

The Eucharist, Communion. In Christian practice, the Eucharist – or Holy Communion – originated in Jesus’ Last Supper and in one of Paul’s genuine letters, I Cor 11:23ff. Most practicing Christians are familiar with the words of institution:  “The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread,” etc. Jesus’ body is the bread, and his blood is the wine. We are instructed to “do this in remembrance of” him.

“The Lord Jesus, on the night he was betrayed, took bread,” etc. Jesus’ body is the bread, and his blood is the wine. We are instructed to “do this in remembrance of” him.

The bread and wine elements, and their symbolism, were present in ritual meals for centuries: “Bread and wine were substituted for the flesh and blood of numerous ancient savior gods, such as Osiris, Adonis, and Dionysus” (Walker, 177). Devotees of Osiris/Serapis ate his body (in the form of bread) “confident that this sacrament would make them divinities in the afterlife by partaking of the divine essence.” His cult was very popular in Rome, but he was frequently worshipped alongside “the Goddess Isis, who was also the Savior’s mother, sister, wife, preserver, and Holy Spirit, all in one” and “the agent of Osiris’s resurrection” (Walker, 216).

Bread – and baking it, too, of course – belonged primarily to the realm of women, at least in the home. Pleading for daily bread – like Christians do in the Lord’s Prayer – was probably a plea to the goddess early on. It was the female deity that “was always the giver of bread, the Grain Mother, the patron of bakers, mills and ovens.” This all-powerful goddess had jurisdiction over the earth and everything in and on it; she appeared in many forms in ancient cultures.  The son of this goddess “was typically the dying-and-resurrected god who personified the grain.” These grain gods “represented the wheat or barley crop at Eleusis and other pagan shrines, where the cycles of growth were controlled by the Great Mother [such as Demeter], who resurrected them from the underground tomb-womb” (Walker, 486).

The son of this goddess “was typically the dying-and-resurrected god who personified the grain.” These grain gods “represented the wheat or barley crop at Eleusis and other pagan shrines, where the cycles of growth were controlled by the Great Mother [such as Demeter], who resurrected them from the underground tomb-womb” (Walker, 486).

Within Christianity, differences around the Eucharist developed. In one example, Episcopalians take the bread (host) in the hands at Communion. However, Roman Catholics did away with this practice and started having the priest put the host directly on people’s tongues because, according to Walker, communicants “often carried it off for later use in magic charms, instead of eating it on the spot” (Walker, 482). Church officials complained that the bread of the Mass was used by witches, sorcerers, and other unsavory people (most of which may have been believed to be women).

Dionysos, the Roman Bacchus, was the deity on the wine side of the story – the wine god. Wine is from grapes, of course, and grapes were viewed as a gift of the goddess.

When it comes to Holy Communion, the roots cannot be traced just to Jesus and Paul in the first century CE but rather to Neolithic times – when people revered nature, human women, female animals and the deity in female form. When we consume the bread and wine in church – or even when we eat any meal – we can perhaps turn our hearts and minds to gratitude toward our earth Mother who provides the grain and the grapes.

Baptism. The next practice to consider is baptism, which is not generally performed weekly but is often done during a Sunday service. As Walker points out, “Baptismal rituals were originally centered on motherhood and the maternal prerogative of name-giving” and initially had to do with mother’s milk (Walker, 169).

Because this topic is vast, we will focus on water, the primary element in Christian baptism. The Book of Common Prayer’s words around baptism and water summarize the theology behind the practice: “Holy Baptism is full initiation by water and the Holy Spirit into Christ’s Body the Church. The bond which God establishes in Baptism is indissoluble. . . We thank you, Almighty God, for the gift of water. Over it the Holy Spirit moved in the beginning of creation. Through it you led the children of Israel out of their bondage in Egypt into the land of promise. In it your Son Jesus received the baptism of John and was anointed by the Holy Spirit as the Messiah, the Christ, to lead us, through his death and resurrection, from the bondage of sin into everlasting life. We thank you, Father, for the water of Baptism. In it we are buried with Christ in his death. By it we share in his resurrection. Through it we are reborn by the Holy Spirit.  Therefore in joyful obedience to your Son, we bring into his fellowship those who come to him in faith, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Now sanctify this water, we pray you, by the power of your Holy Spirit, that those who here are cleansed from sin and born again may continue for ever in the risen life of Jesus Christ our Savior.” The perspective on the rite and on water, incorporating both Christian notions and elements from the Hebrew Scriptures, is thoroughly masculine.

Therefore in joyful obedience to your Son, we bring into his fellowship those who come to him in faith, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Now sanctify this water, we pray you, by the power of your Holy Spirit, that those who here are cleansed from sin and born again may continue for ever in the risen life of Jesus Christ our Savior.” The perspective on the rite and on water, incorporating both Christian notions and elements from the Hebrew Scriptures, is thoroughly masculine.

According to archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, however, water was traditionally in the domain of the goddess, the “life-giving moisture of the Goddess’ body.” Also, all life depends on the water of springs, streams, rivers, rain and dew. From at least as early as the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras, water was depicted with zigzag lines and geometric symbols on figurines, sculptures, vases, altar pieces, and cult vessels. These geometric symbols were often found in conjunction with water bird images – ducks, geese, cranes, and swans – and all were linked to the prehistoric nature goddess (Gimbutas, Language 3, 8, 11-17, 19-21, 25-26).

In earlier times in the history of the church, adult baptism usually happened on the Saturday before Easter. Candidates for baptism, who’d been preparing during the penitential season of Lent, would be submerged in the sunken bath in the middle of the baptistery; they’d then come out of that space to be dressed in white garments as newly born Christians. Then there was a procession, and they were allowed to take their first Communion (Herrin, 67-68).

According to Walker, adult baptism was symbolic of “reentering the womb, to pass through its waters and attain a new birth.” However, the church eventually adopted infant baptism. That effectively took the rite away from mothers and transferred it to male priests – because, in “original sin” thinking of the church, children were demonic because they’d passed through the female body, “and this demonism could only be exorcised by the church’s baptism” (Walker, 169).

Many of us love the rite of baptism, especially when it is administered to infants. However, we might do well to remember that water comes from our great Mother, the earth, and that its relative, mother’s milk, comes from female animals and humans.

Prayers and praying. Next we turn to a religious practice common to most belief systems: praying. We pray privately, communally, in different postures, and so on. Since prayer is a huge topic, we will focus here on the ancient image of a female figure in the orans position – praying with upraised hands.

“Orans” or “orante” means “the praying one.” It was a very common image in Christianity but was mostly associated with male biblical figures in the Roman catacombs (which date to the 2nd to 4th centuries CE) – Noah in the ark, Jonah in the boat and spewed out of the whale, Daniel between the lions, and the three young men in the fiery furnace.

Why did the early Christians use a female figure in these male-themed biblical stories, especially in catacomb art? One clue is that the orante is often found in a nature context, flanked by flowers, trees and plants.  Nature, as we’ve touched on already, is the domain of the goddess – as is the underground, the body of Mother Earth, like the catacombs – and a female figure with upraised arms was in the religious repertory of prehistoric peoples of Old Europe and the Mediterranean. Excavations of Neolithic sites have exposed thousands of female figurines and symbols that have stunning parallels with the orante figure, as we saw earlier (the hunt goddess, the snake goddess and the frog or toad). Another common Neolithic image is the goddess in a birth-giving position – legs spread widely apart and arms upraised (Sjöö and Mor, Cosmic Mother, 212-14; and Gimbutas, Language, 251-55).

Nature, as we’ve touched on already, is the domain of the goddess – as is the underground, the body of Mother Earth, like the catacombs – and a female figure with upraised arms was in the religious repertory of prehistoric peoples of Old Europe and the Mediterranean. Excavations of Neolithic sites have exposed thousands of female figurines and symbols that have stunning parallels with the orante figure, as we saw earlier (the hunt goddess, the snake goddess and the frog or toad). Another common Neolithic image is the goddess in a birth-giving position – legs spread widely apart and arms upraised (Sjöö and Mor, Cosmic Mother, 212-14; and Gimbutas, Language, 251-55).

One theory about the Christian symbolism of the praying female figure has to do with the Roman value of pietas, or the security and peace of filial piety. As we noted, following scholar Graydon Snyder (19-20), the Jewish and Christian figures who need rescuing – Noah, Jonah, Daniel – are depicted in the guise of the orante, especially in catacomb art, because she symbolizes the rescue of threatened Christians by membership in a community of faith protected by a loving God.

Finally, in our treatment of Sunday liturgies, we will consider processions. The act of processing down the aisles of the church at the beginning and end of the service – perhaps a verger, thurifer (carrying incense), or cross-bearer (crucifer) followed by candle-bearers (acolytes), priests, lay leaders, choir and others – takes place in almost all Christian liturgies.  There might also be smaller processions during the service, such as bringing the Gospel down the aisle (into the midst of the people) during Communion.

There might also be smaller processions during the service, such as bringing the Gospel down the aisle (into the midst of the people) during Communion.

There were many parallels in the ancient world. Processions were important aspects of many cults, held in conjunction with public festivals. Processions in the ancient world often included young girls, people playing instruments, public officials, priests and priestesses, clothing for the cult statue being honored, and the animals to be sacrificed (Ferguson, 183). Some of the deities whose cult practices included processions were Isis (Ferguson, 255-56), the grain goddess Demeter and her daughter Persephone at Eleusis (Ferguson, 240-41), and Dionysos/Bacchus (Ferguson, 245). It is probable that the Artemis/Diana cult at Philippi and elsewhere featured evening torchlight processions led primarily by girls, women and priestesses, since one association of this goddess was the moon (Abrahamsen, Women and Worship, 46, 65).

Processions add solemnity, color, drama and often music to Christian liturgies, and indeed to the rites of many religious groups. In the ancient world, processions may have served political and secular purposes, but they helped bring people together peacefully in a celebratory way. Christians may think of processions from a triumphalist position – “Christ has won the victory” (or a similar sentiment) – but in a heterogeneous world like ours, it might be more respectful of our non-Christian neighbors to think of them as an offering of something beautiful and grand to a loving community –without judgment or evangelistic fervor.

Conclusions

By examining the pagan roots of current and traditional Christian practices, we can begin to appreciate the wisdom of our long-ago ancestors. They lived in very different times from ours, but they were in constant, intimate touch with nature, its cycles, its power, and its ability to heal. Evidence from prehistoric times shows that people who revered the deity in female form formed peaceful, advanced and artistic civilizations that lasted for millennia.

Can we think differently, then, about our Christian practices?

Can we think differently, then, about our Christian practices?

- When we are in the presence of the altar, can we think of ancient priestesses overseeing the burning of an offering and the distribution of the food to the people?

- When we next take Communion, can we think of Mother Earth and her bounty in giving us grain for the bread and grapes for the wine or juice?

- When we attend an infant baptism, can we remember that the ritual may have originated in motherhood and life-giving water that was long believed to have been provided by the goddess?

- When we pray with upraised arms, or see others do it, can we think of the birth-giving posture of women and the powerful, all-embracing love and energy associated with the prehistoric nature goddess?

- When we next view or take part in a procession, can we embrace its grandeur and the loving community of which its participants are a part?

We will explore the pagan backgrounds of special liturgies and miscellaneous Christian practices in our next post.

Resources (for both posts)

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Goddess and God: A Holy Tension in the First Christian Centuries. Marco Polo Monographs 10. Warren Center, PA: Shangri-La Publications, 2006.

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Women and Worship at Philippi: Diana/Artemis and Other Cults in the Early Christian Era. Portland, ME: Astarte Shell Press, 1995.

Boswell, John. Same-sex Unions in Premodern Europe. New York: Villiard Books, 1994.

Brooten, Bernadette J. Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. New York: Penguin Books, 1982; first ed., Viking Press, 1959.

Church Pension Fund. The Book of Common Prayer. New York: The Church Hymnal Corporation, 1986.

Collart, Paul and Pierre Ducrey. Philippes I: Les reliefs rupestres. Athens and Paris: BCH Supplement 2, 1975.

Eisler, Riane. The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future. San Francisco, Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987.

Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds of Early Christianity, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1993.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991.

Glancy, Jennifer A. Slavery in Early Christianity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006. Original hardcover edition Oxford University Press, 2002.

Herrin, Judith. Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Kraemer, Ross Shepard and Mary Rose D’Angelo, eds. Women and Christian Origins. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lefkowitz, Mary R. and Maureen B. Fant. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Mitchell, John. The Earth Spirit. London: Thames and Hudson, 1975; New York: Avon Books, 1975.

Pervo, Richard I. Dating Acts: Between the Evangelists and the Apologists. Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 2006.

Reis, Patricia. Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. New York: Continuum, 1991.

Sjöö, Monica and Barbara Mor, The Great Cosmic Mother. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987.

Snyder, Graydon F. Ante Pacem: Archaeological Evidence of Church Life Before Constantine, revised edition. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2003.

Underwood, Guy. The Pattern of the Past. London: Museum, Press, 1969; London: Abacus, 1972.

Walker, Barbara G. The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988.