As we continue living in our dark, challenging, turbulent times, we always need to stay balanced and take solace and comfort from the beauty around us. Here we will look at some examples of beautiful works of art – mosaics – from the Roman Imperial era. Like our times, the first few centuries of the Common Era had its challenges, evils and threats, but also many redeeming, even uplifting, features. Mosaics are among those features that we can admire and from which we can take inspiration.

An in-depth discussion of mosaics is beyond the scope of this post, but we can make a few general points.

- In the first four centuries CE, decorated pavements were often made of opus tessellatum, which means made with tesserae, more or less roughly shaped cubes cut from various materials (D.J. Smith, 116).

- Most tesserae were made from black, white and colored marbles and other stones and tile. Occasionally they are also made of clear and colored glass and sometimes pottery (D.J. Smith, 116).

- The tesserae “were set as closely together as possible in a bed of fresh, fine mortar, on a firm foundation or base” (D.J. Smith, 116; Johnson, 7).

- Thousands of mosaics have been recorded and are housed in museums and other venues all over the world.

- A large mosaic pavement generally took approximately several months’ time in initial preparation in a workshop followed by a few weeks of work on-site (Johnson, 9).

- Materials used included chalk, limestone, brick, marble, sandstone, and ironstone (Johnson, 10).

- It is likely that professional mosaic designers were hired, and pattern books are known to have existed. A patron could probably choose his (occasionally her) design from these books, and “slavish copying” appears to be rare (Johnson, 10-11).

- “Mosaic floors were fashionable throughout the Empire… Like wall-paintings, mosaics added to the prestige of the house and could indicate, through careful choice of subject, the patron’s interests or the function of a particular room” (Walker, Roman Art, 53).

Here we will offer a few secular and sacred examples from Great Britain, Austria, Italy, and Greece. Some of them date earlier, to the Hellenistic era, and may well have been known and visible to the people of the Roman Empire. A list of resources for further reading is included below.

Great Britain

Part of the hare mosaic, second half of the fourth c. CE, Corinium Museum, Gloucestershire, England.

Mosaic floor in bath, Chedworth Roman Villa, England

Austria

Roman-era mosaic, crypt of Salzburg Cathedral

Italy: Ravenna

Apse mosaic, St. Apollinare in Classe, 6th c., St. Apollinarius flanked by 12 sheep

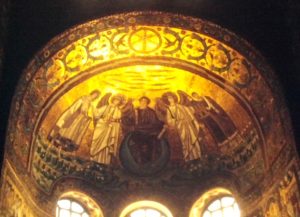

Baptistery of the Arians, 5th c.

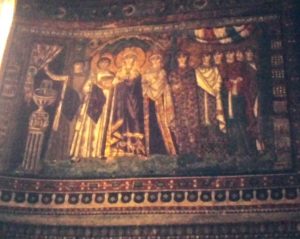

San Vitale Basilica mosaic, 6th c.

San Vitale Basilica mosaic, 6th c.

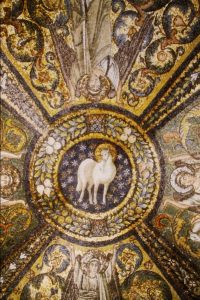

San Vitale Basilica, Christ as the Lamb apse mosaic, 6th c.

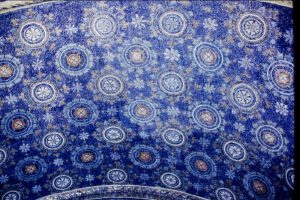

Galla Placidia Basilica mosaic, 5th c.

Galla Placidia Basilica mosaic, 5th c.

San Apollinare Nuovo Basilica mosaic, Christ (haloed) with Peter and Andrew, 6th c.

Italy: Pompeii/Naples

Mosaic from Pompeii, 1st c., now in the Naples Archaeological Museum

Greece

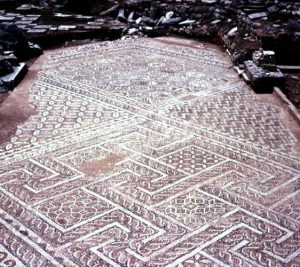

Mosaic floor at Macedonian (Vergina) palace, 4th c. BCE

Roman-era forum, with stoas, Thessaloniki

Floor mosaic, Octagon Basilica, Philippi, 4th c.

Floor mosaic, Octagon Basilica, Philippi, 4th c.

Floor mosaic, early Christian church, Delphi

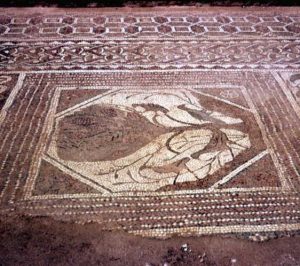

House mosaic, Delos, late 2nd c. BCE

Dionysos and panther, Delos, ca. 120-80 BCE

Let us bask for a few moments in the beauty of these works of art and appreciate the beauty around us as we navigate our personal, local, national and worldwide challenges.

Resources

Henig, Martin, ed. A Handbook of Roman Art. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 1983

Johnson, Peter. Romano-British Mosaics. First published 1982; second ed. 1987. Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications, Ltd., 1995.

Kolarik, Ruth and Momcilo Petrovski. “Technical Observations on Mosaics at Stobi,” in James Wiseman and Ðorde Mano-Zisi, eds., Studies in the Antiquities of Stobi, Vol. 2, 65-106. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

McWhirr, Alan. Roman Crafts and Industries. Aylesbury, UK: Shire Publications Ltd., 1988.

Megaw, A.H.S. and E.J.W. Hawkins. The Church of the Panagia Kanakariá at Lythrankomi in Cyprus: Its Mosaics and Frescoes. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, 1977.

Michaelides, Demetrios. “The Early Christian Mosaics of Cyprus.” Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 52, No. 4 (December 1989) 192-202.

Smith, D.J. “Mosaics,” in Martin Henig, ed., A Handbook of Roman Art. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 1983, 116-38.

Smith, Robert Houston. “Decorative Geometric Designs in Stone: The Rediscovery of a Technique of Roman-Byzantine Craftsmen.” Biblical Archaeologist (Summer 1983) 175-86.

Walker, Susan. Roman Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991.

Weiss, Zeev. “The Sepphoris Synagogue Mosaic: Abraham, the Temple and the Sun God – They’re All in There,” Biblical Archaeology Review, Vol. 26, No. 5 (September/October 2000) 48-61, 70.