Many years ago when I was in divinity school, my favorite professor, the late Dieter Georgi , spoke to us in his classes about utopia. He saw utopia everywhere in Scripture. Dieter as a 15-year-old German was drafted by Hitler’s Navy and survived the bombing of Dresden; he lived his whole life with a sense of responsibility for what his fellow Germans did to the Jews. He was also happily married for almost 50 years before he died, and he and his wife raised five wonderful, accomplished children. He was no naïve, privileged, ivory-tower intellectual; he was grounded in reality – part of the reason his talk of utopia was not idle fantasy.

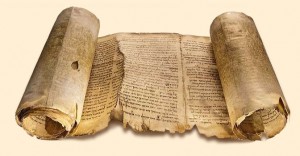

While I trusted Dieter’s take on utopia on the face of it, and I could see signs of utopia in the writings of Paul and the lives of the first Christians, it wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I had “ah ha” moments when hearing other readings from Hebrew Scripture and the New Testament.

- Isaiah 50 is in a portion of Isaiah – chapters 40-55 – addressed to an exiled community in Babylon during the 6th century Before the Common Era (BCE). If we imagine what it would have been like to be torn from our homeland and exiled into a new land, we can begin to see the power and hopefulness of the prophet’s message: “Despite the fact that I am being tortured and insulted, God is there and will assist me.” Perhaps Isaiah’s listeners thought he was a bit crazy to have so much trust in his God!

- The Letter to the Hebrews is set in the early church somewhere in the Roman Empire after the death of Paul and probably before the fall of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE. The addressees, perhaps Jewish Christians in Palestine or Syria, are imperial subjects; the emperors at this time would have been Nero, Vespasian or the three emperors who ruled in the chaotic years 68-69. The recipients of the Letter to the Hebrews would most likely have come from the lower strata of society and thus knew of hardship on a daily basis. The author of the letter reminds his listeners, especially in Chapter 12, verses 1-3, that Jesus too had suffered – but has won the victory.

- John 13:21-32 is a portion from Jesus’ “Farewell Discourses.” John is a complex Gospel compiled over several decades in the Roman imperial period and circulated in its final form starting in the late first century CE. This section of John is all about betrayal – and glorification. From the depths of Jesus’ despair that a follower, not a stranger, would send him to his death comes the certainty that betrayal and death do not have the last word. How do we, who also know betrayal and despair, find that lasting, abiding certainty?

If we listen to the Bible from the vantage point of agrarian peoples, even slaves, living at subsistence levels, we can begin to feel the power of their utopian visions. The dictionary defines utopia as any condition, place or situation of social or political perfection. When we think of utopia, we may think of small, idealistic communities such as the Amish or Shakers. They are wonderful to strive for but almost impossible to attain. How, then, do we reconcile the obvious signs of a world gone horribly awry and our feelings of pain, despair and anguish with the seemingly impossible joy, conviction, and hope that seeps through our ancestors’ words and lives?

I have become convinced in recent years that the search for utopia and social justice in our society works best when it is hand in hand with a mystical, contemplative striving for an abiding inner peace and joy. I believe that those of us who call ourselves Christians are called to seek justice for ourselves and others at macro levels – in our society – at the same time that we are called to seek inner peace, spiritual growth and a daily walking with the Divine.

At the base of this quest is “practice.” Coming together for worship services is one practice; over time, communal worship seeps into our soul – the words of Scripture, the messages from the pulpit, the music, the Eucharist, the service to others in our community, and the fellowship.

Then there are the practices done in the home or with small groups – grace before meals; prayers at bedtime; Bible study. What has happily been revived in recent years in Catholic and Protestant circles are practices such as spiritual direction, or walking together with a spiritual friend; contemplative or centered prayer; praying with icons; silent retreats; meditation and yoga; lectio divina; chant; and probably many others. Resources and tools such as books, religious societies of nuns and monks, spiritual directors, and retreat centers are more available than ever in many communities.

The blending together of the striving for social justice and contemplative practice all takes time and commitment, and there are often stops and starts on the journey. Sitting with an icon and a candle in a dark room for 20 minutes does not usually produce immediate effects! A silent retreat might be excruciating at first – “yikes, how can I go so long without talking?!” Working with a spiritual director may feel at times like we are moving farther from God, not closer. But over time, something starts to happen, and the despair of losing a loved one, or conflict at work, or threats of violence, natural catastrophes and financial disaster recede just a little bit and are replaced by a stronger assurance that God is present, we are surrounded by love and all will be well.

Somehow our ancestors knew all this and bequeathed to us the astounding literature of Judaism, Christianity and other faiths. May we learn from them about their utopian visions and find ways to bring those visions to life in our own age.