We have met some of the women of Graeco-Roman antiquity in the past, especially those that may shed light on the early Jesus movement. We have looked at St. Paul’s female colleagues, a female ceramicist from Crete, the first apostle Mary Magdalene, several women named Salome, the sainted Thecla, and priestesses in pagan religion. This time we will take a look at a selection of occupations for which we have evidence that may be somewhat unusual or surprising.

Most of the evidence for these women comes from inscriptions, many associated with graves or statues, and these inscriptions have been found all over the Empire and over a wide span of time.

Aurelia Nais, a fishmonger

- “Aurelia Nais, freedwoman of Gaius, fishmonger in the warehouses of Galba. Gaius Aurelius Phileros, freedman of Gaius, and Lucius Valerius Secundus, freedman of Lucius, [dedicated this altar].”

(From a 1st-century CE Roman epitaph. Lefkowitz and Fant, 170)

(From a 1st-century CE Roman epitaph. Lefkowitz and Fant, 170)

Irene, a salt vendor

- Inscription from Roman Athens. (2nd-3rd century CE. Lefkowitz and Fant, 171)

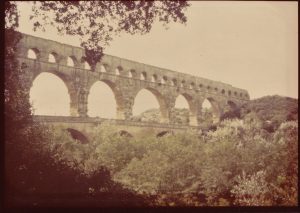

Modia Quintia, who built an aqueduct

- “The town council decreed a statue of Modia Quintia, … perpetual priestess, who, on account of the honour of the priesthood, adorned the portico with marble paving, coffered ceilings and columns, exceeding in cost her original estimate with an additional contribution and quite apart from the statutory entry fee [for the priesthood] and also [built] an aqueduct.”

(2nd-3rd century CE inscription from Africa. Lefkowitz and Fant, 158)

(2nd-3rd century CE inscription from Africa. Lefkowitz and Fant, 158)

Scholasticia, who restored two public baths

- “You see here, stranger, the statue of a woman who was pious and very wise, Scholasticia. She provided the great sum of gold for constructing the part of the [buildings] here that had fallen down.” (From Ephesus, Christian period. Lefkowitz and Fant, 159)

Flavia Publicia Nicomachis, city founder and benefactor

- “The council and the people, to Flavia Publicia Nicomachis, daughter of Dinomachus and Procles. . . their benefactor, and benefactor through her ancestors, founder of our city, president for life, in recognition of her complete virtue.” (2nd-century CE inscription from Asia Minor. Lefkowitz and Fant, 158)

Pamphile, a writer

- “Pamphile was an Epidaurian [from Epidauros, Greece], a learned woman, … who is also said to have been an author of books… She wrote historical memoirs in thirty-three books, an epitome of Ctesias’ history in three books, many epitomes of histories and other books, about controversies, sex, and many other things.” (From an ancient encyclopedia, 1st-century CE. Lefkowitz and Fant, 159)

Berenice the magistrate

- “The resolution of the prytaneis approved by the council and the people: Whereas Berenice, daughter of Nicomachus, wife of Aristocles son of Isidorus, has conducted herself well and appropriately on all occasions, and after she was made a magistrate, unsparingly celebrated rites at her own expense for gods and [human beings] on behalf of her native city…. Voted… to crown her with the gold wreath which in our fatherland is customarily used to crown good women.” (2nd-3rd-century CE, Syros. Lefkowitz and Fant, 261)

Magnilla, a philosopher

- “For Magnilla the philosopher, daughter of Magnus the philosopher, wife of Menius the philosopher.” (2nd-3rd-century CE from Apollonia. Lefkowitz and Fant, 160)

Physicians – freeborn, freedwomen or slaves

Physicians – freeborn, freedwomen or slaves

- “Antiochus, daughter of Diodotus of Tlos, awarded special recognition by the council and the people of Tlos for her experience in the healing art, has set up this statue of herself.” (1st-century CE inscription from Lycia. Lefkowitz and Fant, 161)

- “You rush off to be with the gods, Domnina, and forget your husband. You have raised your body to the heavenly stars. [People] will say that you have not died but that the gods stole you away because you saved your native fatherland from disease. Goodbye, and rejoice in the Elysian fields. But you have left pain and eternal lamentations behind for your loved ones.” (2nd– or 3rd-century CE inscription from Asia. Lefkowitz and Fant, 161)

- “To my holy goddess. To Primilla, a physician, daughter of Lucius Vibius Melito. She lived forty-four years, of which thirty were spent with Lucius Cocceius Apthorus without a quarrel. Apthorus built this monument for his best, chaste wife and for himself.” (1st– or 2nd-century CE inscription from Rome. Lefkowitz and Fant, 161)

- “Minucia Asste, a doctor, freedwoman of Gaia.” (Rome, 1st-2nd-century CE. Lefkowitz and Fant, 161)

- “Venulaia Sosis, a doctor, freedwoman of Gaia.” (Rome, 1st-2nd-century CE. Lefkowitz and Fant, 161)

- “Melitine, a doctor, [slave] of Appuleius.” (Rome, 1st-2nd-century CE. Lefkowitz and Fant, 161)

- Also, a woman named Panthia from Pergamon in the second century was highly honored at her death by her husband, who says of her “you guided straight the rudder of life in our home and raised high our common fame in healing – though you were a woman you were not behind me in skill.” (Lefkowitz and Fant, 162)

Conclusions

Knowing in more detail about the lives of women in the Roman Empire can teach us a great deal.

- Historically the study of ancient societies has focused on men and men’s lives. Knowing about women (and children and slaves as well) helps us “fill in the blanks” of those societies, especially those societies that have had so much impact on Western civilization.

- The lives of women in antiquity were richer and more interesting than we may have been led to believe. Women were not just nameless wives and mothers living in isolation within the confines of the home, but often intimately involved in the more public aspects of life.

- While we may know that women were nurses and midwives in antiquity, we should also know that they could also function as highly-respected physicians.

- While we may know that women had significant roles in their homes, including child-rearing, we should also know that they were esteemed philosophers and authors.

- Once we realize that women had wider roles in the ancient world, especially the world out of which Christianity emerged, we realize that the suppression of women – over time and even continuing into our own – deprives societies (and our religious institutions) of their many gifts and talents. Honoring the lives of women, in contrast, and allowing them to explore their lives to the fullest, not only pays those women respect but also enriches everyone’s life.

- Seeing that women in antiquity participated in many walks of life, and that many of those women were highly revered by their peers and relatives, can help us moderns see ourselves in those long-ago women.

That is, ancient women may well have struggled and suffered – their occupations were often difficult, and many women, like men, were enslaved (and potentially abused) for portions of their lives – yet the reason we know about them is due to the loving and admiring inscriptions that have survived for millennia. May we continue to honor and remember the lives of all women who have given back to their communities.

That is, ancient women may well have struggled and suffered – their occupations were often difficult, and many women, like men, were enslaved (and potentially abused) for portions of their lives – yet the reason we know about them is due to the loving and admiring inscriptions that have survived for millennia. May we continue to honor and remember the lives of all women who have given back to their communities.

Resources

Boulding, Elise. The Underside of History. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1976; rev. ed., Sage Publications, 1992.

Kraemer, Ross Shepard and Mary Rose D’Angelo, eds. Women and Christian Origins. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lefkowitz, Mary R. and Maureen B. Fant. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Meyers, Carol, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds. Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Pomeroy, Sarah. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1975.

Walsh, Elizabeth Miller. Women in Western Civilization. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co., Inc., 1981.